They come in crumpled paper bags or inside empty water bottles. Sometimes, they come in buckets. Whatever the vessel, when the dirty needles are handed in, they’re traded for clean ones.

They come in crumpled paper bags or inside empty water bottles. Sometimes, they come in buckets. Whatever the vessel, when the dirty needles are handed in, they’re traded for clean ones.

In the 28 years since it opened, the core mission of the Tacoma Needle Exchange has stayed the same: to stop the spread of disease among intravenous drug users.

But the job, and the challenges, have changed. With surging rates of new infections, hepatitis C has become one of the chief public health concerns among those who shoot up heroin and other drugs, and more and more people are coming to the exchange each year.

The exchange provides clean needles and other equipment — a strategy known as harm reduction — but workers there also help people get into treatment and encourage them to quit or cut back.

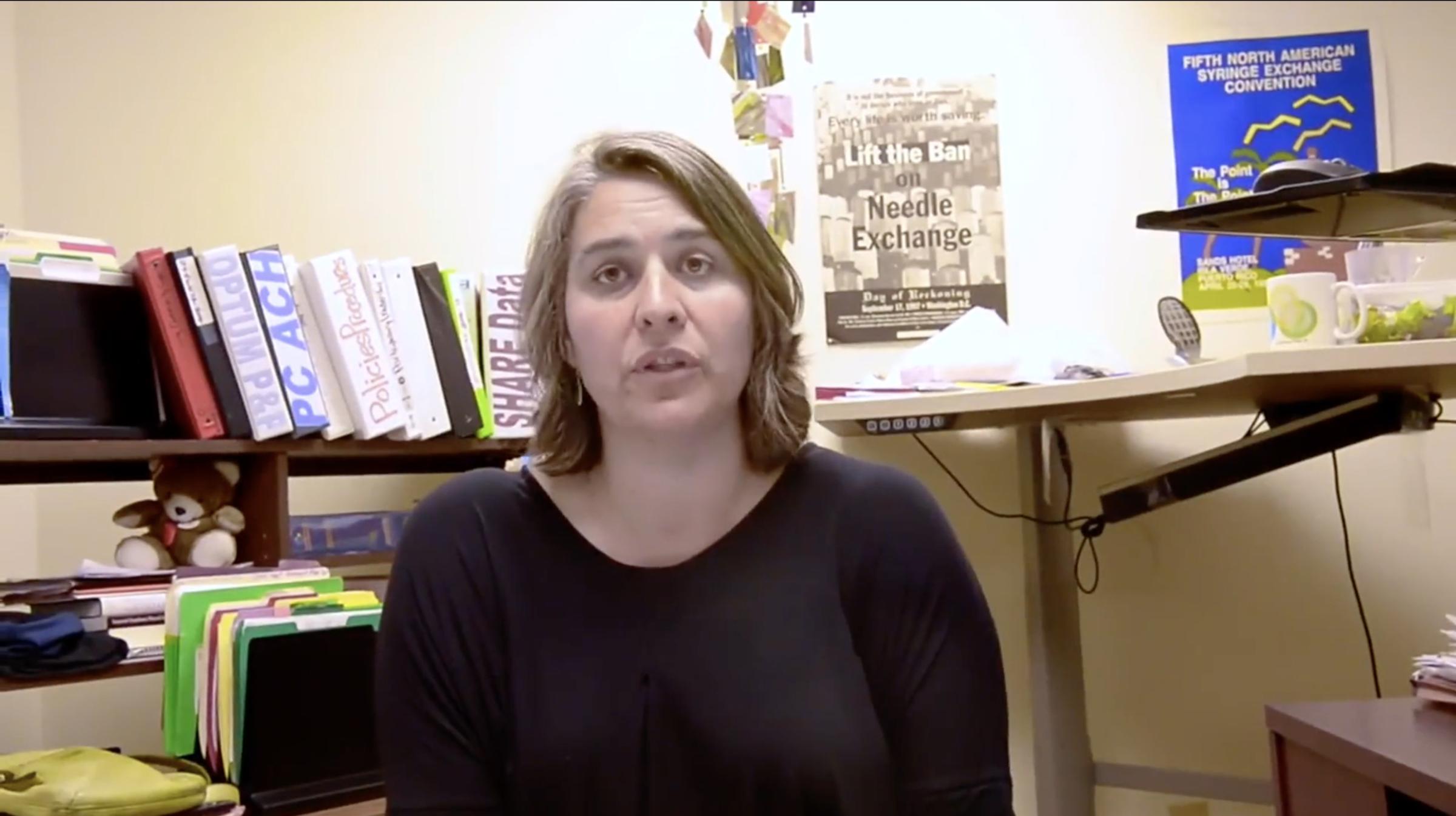

Most of the funding for the exchange comes from the state Department of Health and is funneled through funding for HIV prevention, said Alisa Solberg, executive director of the Point Defiance AIDS Project, which operates the needle exchange. Funding to fight hepatitis C hasn’t caught on in the same way, she said.

“I would say that when we first started the needle exchange here in Tacoma, the main concern was HIV and deaths associated with HIV. Now there are broader health concerns. So, overdose, hepatitis C, injection-related wounds,” Solberg said.

“And I think that there’s an argument for the fact that stigma is one of the biggest concerns. ... As we stigmatize people, and they’re forced to hide what they do, then it’s very difficult to address those concerns from a public health perspective.”

When Tacoma public health legend David Purchase started handing out clean needles in the late 1980s, he was fighting the spread of the AIDS epidemic that was killing intravenous drug users in droves. Working as the first legally sanctioned needle exchange in the country, he would give people clean syringes from his TV tray and folding chair set up downtown and safely discard used ones.

When Purchase started in 1988, “They were dying of AIDS faster than he could get them into treatment,” said Dennis Sayler, the lanky, sandy-haired man who today runs the nondescript needle exchange van at 14th and G streets.

Purchase died of pneumonia in 2013 at age 73. He worked at the exchange until his death, Solberg said.

These days, Sayler opens the doors of the van at 14th and G for three hours a day, four days a week. Another needle exchange van operates out of the county health department parking lot. People drive in or wander up to trade in dirties for cleans, and pick up wound care kits or naloxone, the drug that can stop an opioid overdose before the person dies.

Not all are drug addicts. On a recent Monday, a diabetic man wandered up looking for supplies that his insurance no longer covers, Sayler said.

In the years the exchange has operated, heroin use has waned and waxed, and the AIDS mortality rate has dipped as new antiretroviral drugs and public awareness helped loosen its grip on vulnerable populations.

“We’ve almost worked ourselves out of a job,” Solberg said. Mostly, she means funding. Money for their work still largely comes from money dedicated to HIV prevention, she said, even as concerns about HIV have been eclipsed by concerns about hepatitis C, overdoses and wound infections. The state Department of Health gives the exchange about $360,000 a year in funding and supplies, Solberg said. They also have a contract with health services provider Optum for $208,000 for community outreach, education and for referral to health and social services for the people they serve.

The exchange’s work is much broader now than when they started, and in the office on Dock Street, colorful cardboard boxes that hold the tools of their trade are stacked ceiling-high: Inside are clean syringes, naloxone, biohazardous waste buckets, condoms, wound care kits, sterile single-use water packets, little tin cookers and clean swabs of cotton for drug injectors.

The opioid epidemic has changed the job, too. Heroin’s resurgence as a cheap, easy-to-get alternative to prescription pain pills has led the surge in demand for clean needles and a bevy of other health services. With it, a new concern has emerged: hepatitis C, more easily transmissible than HIV.

The Point Defiance AIDS Project exchanged about 1.7 million needles between July 1, 2015, and June 30, 2016, and the group said that number increases by about 10 percent each year.

“A lot of my friends that mainly do heroin have hep C,” said Shawn Chaplin, a 41-year-old who is a regular visitor to the needle exchange van. Chaplin injects meth — not heroin — and every few months he comes to the van to get tested for exposure to HIV and hepatitis C. On a Thursday early this month, he sat down inside the van, got his finger pricked, and waited about 20 minutes.

He tested negative for both. But the man who came just before him tested positive for hepatitis C exposure, said Madeline Meisburger, a community outreach worker with the Point Defiance AIDS Project.

“Now we’re finding that the hep C rates are surpassing the HIV rates, so it’s almost as if hep C is the new disease epidemic,” Meisburger said. “We’re testing, but we’re also educating about prevention. We have all the tools here and all the education you need to not get this horrible disease, so let’s start from the very beginning with these good injection practices.”

In the early days, hepatitis C wasn’t really on the radar. Purchase started by handing out clean needles and alcohol wipes, Solberg said, which were effective in protecting against HIV. It wasn’t until the late 1990s that the exchange was allowed to distribute other injection supplies, such as clean cookers (the metal container used for mixing and heating heroin before injection), tourniquets and cotton to fight bloodborne viruses like hepatitis C that can live outside the body for days or even weeks.

“We were not able to respond to the hepatitis C epidemic the way we were able to respond to the HIV epidemic,” Solberg said. “The HIV epidemic, we responded with the syringe exchange, but we weren’t able to distribute the other clean works until later in the epidemic, until hep C had really taken hold in the community.”

Today, Tacoma-Pierce County Health Department officials are “absolutely worried” about the spread of hepatitis C, said Kimberly Desmarais, viral hepatitis coordinator for the Health Department. The fact that her title exists proves it: Her position was created this year in response to the growing number of acute hepatitis C infections, Desmarais said.

Pierce County’s rates of acute — or short-term — hepatitis C infections is among the highest in Washington and higher than the state’s rate, with two infections for every 100,000 residents in 2014. That’s quadrupled from an acute infection rate of 0.5 percent in 2010. And though hepatitis C begins as a short-term illness that may not show symptoms, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates that of every 100 cases, 75 to 85 will become long-term or chronic infections.

Of those, 60 to 70 will go on to develop chronic liver disease. Between five and 20 of those people will develop cirrhosis over 20 to 30 years, the CDC says, and between one and five people will die from cirrhosis or liver cancer. It’s a costly disease and one that can cut down life expectancy by decades, health officials say.

“We are taking it very seriously,” Desmarais said. “In 2015, Washington state had 64 acute hepatitis C cases that were diagnosed that met the criteria. Pierce County had 22 of them, and that’s over a 200 percent increase for us since 2013.”

In a 2015 drug injector health survey by the University of Washington’s Alcohol and Drug Abuse Institute, 57 percent of the 77 people surveyed in Pierce County said their addiction started with opiate pills before they turned to injecting heroin. And 39 percent admitted to sharing injection supplies — not just needles — with at least one person in the past three months.

The study was done statewide, with 1,036 total participants. Those users, who were interviewed at needle exchange locations, were asked about how many syringes they’re picking up, whether they have health care, whether they’ve witnessed or experienced an overdose, and about their chief health concerns, among dozens of other questions.

In that study, 88 percent of people surveyed in Pierce County said they have been tested for hepatitis C, and 92 percent said they have been tested for HIV.

Desmarais said the rate of acute hepatitis C infection in Pierce County is likely to see another bump this year: There have already been 19 confirmed cases in the county in 2016, she said. About 95 percent of the cases diagnosed between 2010 and 2014 were IV drug users, according to the state Department of Health.

“The acute rates are mostly in people age 18 to 29, who have most likely contracted it through injection drug use,” Desmarais said. “One of the things we’re really concerned with is that opioid addiction leads into heroin and injection drug use.”

Brian Bennett is another regular who dropped by the van on an early August Thursday looking for clean supplies, half a watermelon in hand. Bennett, 31, has lived in Tacoma his whole life, and said he started using heroin when he was 18. He does it four or five times a day, and found out a year ago that he has hepatitis C. He hasn’t been to the doctor and hasn’t felt sick, but said he knows it’s a disease that could have long-term implications.

“I was so into my addiction that I wasn’t thinking about my life. I was using other people’s needles,” Bennett said. “I’m just letting it take its course. It’s my problem. Nobody else’s. I was devastated. I was upset. But it happens — it happens in the kind of stuff that I do.”

Overdoses and infections also happen. While he waited for his test results outside the van, Chaplin talked with Sayler about a regular of the exchange who died days earlier. Chaplin said she’d had a blood infection from an abscess, a common result of shooting up with nonsterile injection supplies, like dirty water or needles. The woman, who was in her 30s, had been trying to get into treatment, Chaplin said.

“We really have a heart for these people, we don’t judge where they are in life,” Meisburger said. “We’re going to treat them the same as everyone else. It’s really hard when this stuff happens. … There’s no pictures of her, there’s no memorial.”

Sayler, Meisburger and others at the Point Defiance AIDS Project try to encourage their clients to do anything but inject drugs, because that’s the easiest way to get abscesses and infections. Any method is preferable to the needle, they preach. They help them get into treatment, drive them to doctor appointments, provide testing, make home deliveries of clean supplies, sign them up for health care, get them in touch with mental health services, and try to get them to cut back.

They also teach them about the signs of overdose and give quick trainings on how to administer naloxone, with some success. Since the needle exchange started offering it to clients in February, more than 280 kits have been distributed and 26 overdose reversals have been reported.

But sometimes, people disappear. After months or years of dropping by several times a week, they stop coming altogether. Most of the time, Meisburger doesn’t know if it’s because they got clean, or because they got sick, or because something happened to them.

“Sometimes you don’t even know their name — you can know someone for a year and never even know their name,” Meisburger said. “But for whatever reason, you just really hold on to that person and you really care about them. It’s really hard. It’s kind of also why you keep going and doing this for other people, because you don’t want it to happen.”